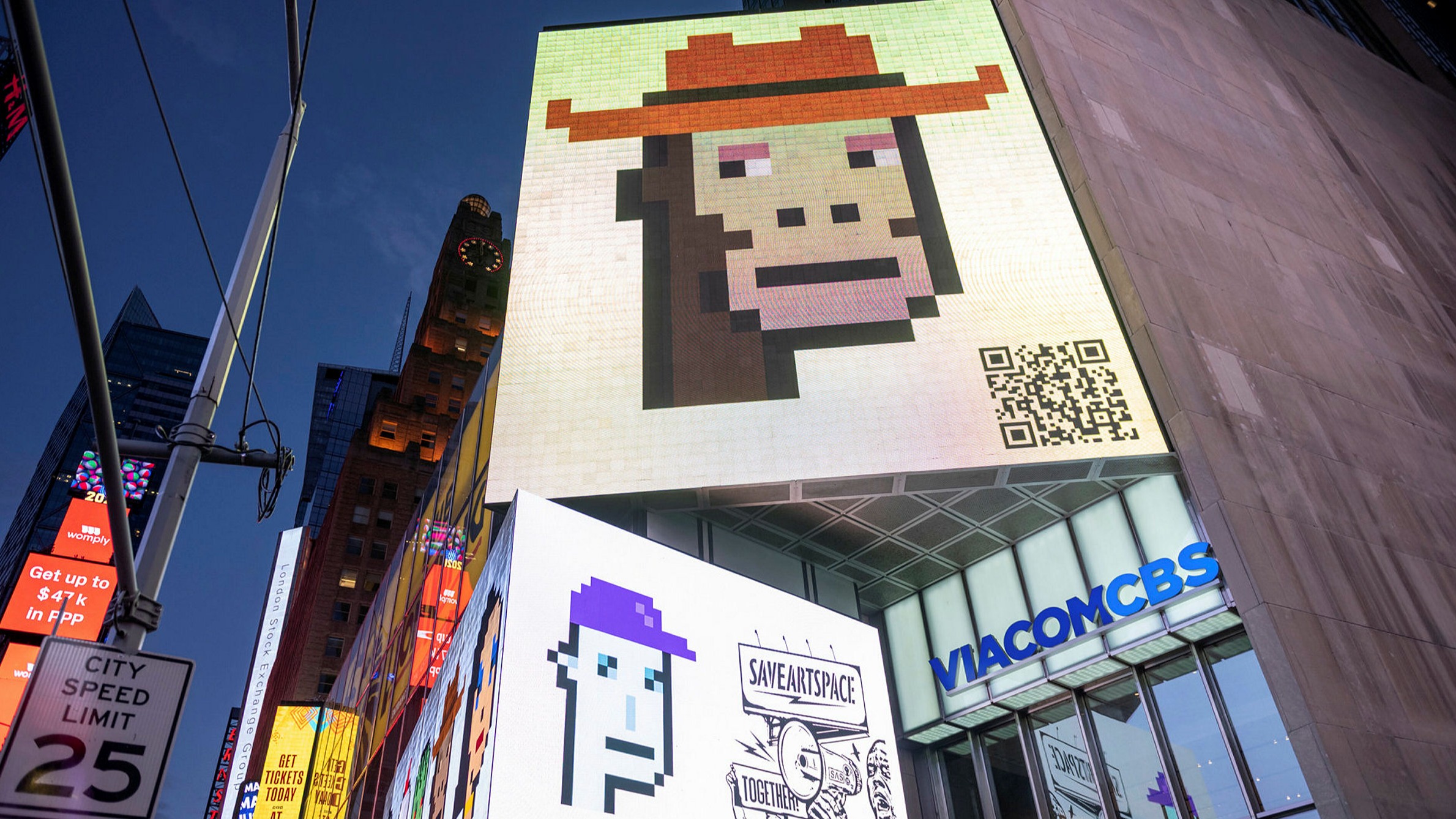

Tech executives and crypto enthusiasts are buying digital collectibles not just for investment — but as art.

In early 2021, Dylan Field, chief executive of San Francisco-based design software group Figma, sold a digital collectible — a non-fungible token (NFT) — for more than $7.5mn.

He had bought the CryptoPunk, a pixellated blue alien avatar smoking a pipe, several years before the market mania — for around $15,000.

He has since built up a porfolio of about 600 NFTs from various collections and artists, many of which are about more than investment: some NFTs can operate like “participatory art experiments”, he says, where buyers can get involved in creating new art together. “The work is not static. It’s a story being told. And that to me is the most interesting use of the technology.”

Field is one of a new breed of investors on the West Coast in the burgeoning digital art world, combining tech savviness and finance chops not just to collect works to flip for profit, but also to hold and display, often as their profile picture (PFP) on Twitter, as Field does.

Tech executives, venture capitalists and crypto enthusiasts alike are wielding them to showcase their allegiance to a particular artist or collection or convey wealth, status and online clout.

In doing so, many claim they are establishing a new kind of art market that does not rely on the gatekeepers of traditional art, and betting that one day we will live more of our lives online in avatar-filled virtual spaces, or metaverses.

It comes as the wider market for NFTs — essentially digital ownership certificates registered on an immutable blockchain — surged to more than $40bn in 2021, in what critics have cast as a speculative bubble.

“Profile pics in general have always been a way for us to represent ourselves digitally . . . what community we’re part of . . . in the same way we wear clothing,” says Mikhael Naayem, co-founder and chief business officer of Dapper Labs, a blockchain company that makes the CryptoKitties NFT collection and NBA Top Shots, digital tokens representing basketball game highlights.

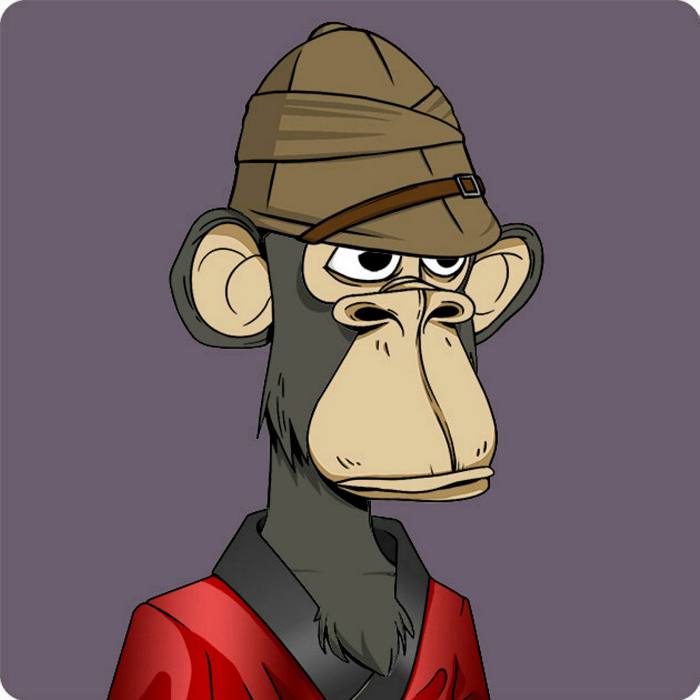

While there are many emerging use cases for NFTs, such as establishing royalties for music, typically NFT PFPs are avatars of human or animal faces — from cats to penguins to apes — and the most popular cost and trade at hundreds of thousands or millions of dollars.

Many collections come with perks, such as invites to private chat rooms on messaging apps Discord or Telegram or passes to exclusive parties and meetups.

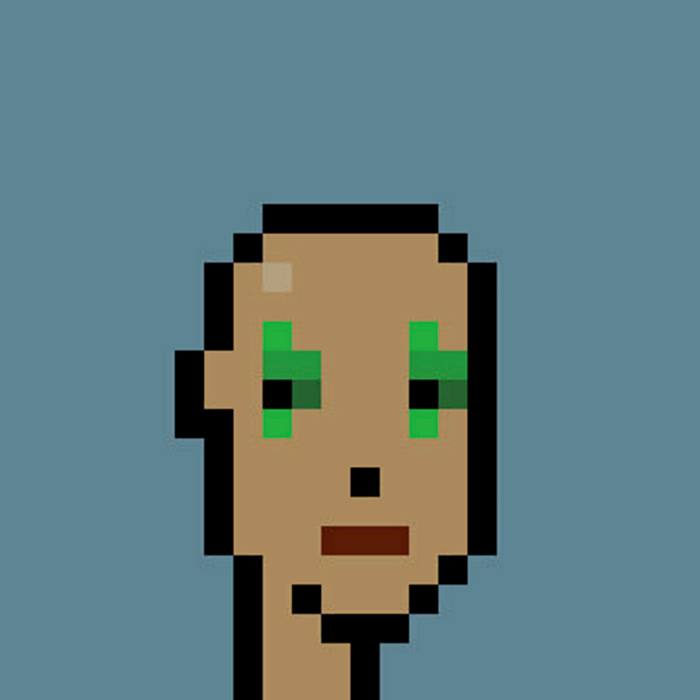

All collections have their own distinct identities and flair. For example, owning a CryptoPunk, a collection launched by Larva Labs consisting of algorithmically generated pixellated faces, often signals an affinity with libertarian politics and concerns about censorship.

After complaints that CryptoPunks had failed to be diverse by skewing largely towards male avatars and not including non-binary avatars, a collection called ExpansionPunks was created based on the CryptoPunk aesthetic but seeking to address those issues.

Collectors describe one of the most prolific collections, the Bored Ape Yacht Club, as having a fraternity-esque quality to it. When users buy their cartoon primate for at least a six-figure sum, they typically take to Twitter writing that they’ve “aped up” or using the hashtag #apefollowape to encourage others to follow them online.

While this new model does not rely on the gatekeepers of the traditional art world, such as auction houses, curators and galleries, purchasing NFTs can be cumbersome and requires tech savviness. They must be bought in cryptocurrency on an NFT digital marketplace, the biggest of which is called OpenSea, and held in a special digital wallet.

There are also unpredictable transaction fees, known as “gas fees”, which are required to mint or purchase an NFT and can fluctuate depending on demand.

Hiten Shah, co-founder and chief executive of security-software company Nira, showcases a PFP of a lion, with dollar signs in its eyes and a rainbow mane to his quarter of a million Twitter followers. For him, diving into the freewheeling world of NFTs over the past six months has made him money, but also friends.

“The real analogy is that this is like Facebook Groups on steroids, with financial incentives,” says Shah, who first began seriously investing in NFTs last summer and has since built up a 1,000-strong collection. “I’ve made an incredible amount of relationships. That trumps everything else about this in my mind.”

Others are merely testing the waters. “I’ve experimented by purchasing a few PFP NFTs, looking at them less as an investment and more as a way to learn about these different projects’ communities and because I’ve liked the particular piece,” said Nikhil Basu Trivedi, co-founder of venture capital group Footwork, whose Twitter PFP is a heavily pixelated smoking figure with red sunglasses. “I think as a VC one has to be playing around with what could potentially be the next big thing to have a prepared mind when meeting founders building in it.”

But there are numerous dangers to entering the fast-paced and freewheeling world of NFTs, which does not offer consumer protections. Tegan Kline, co-founder of crypto group Edge & Node and former investment banker at Bank of America, warns investors of big hacks and the highly engineered scams that are emerging in the NFT sector, such as “rug pulls”, where founders make off with funds.

“We need to check ourselves not to become greedy, and stay educated on the types of scams out there. If it seems too good to be true, it is,” says Kline, who owns a CryptoPunk.

Tegan Kline owns this CryptoPunk but warns about NFT scams © CryptoPunk. Courtesy Tegan Kline

One collector who goes only by the name of Schmrypto on Twitter and who says he “dumped pretty much all my net worth into cartoons, cats and monkeys at just the right moment”, has decided not to link his real-world identities to his social profiles in order to better protect himself.

Investors in the space continue to face pushback from the mainstream art world. There are critics who argue that NFTs are worthless JPEGs that can be copied, therefore the market is boosted by false scarcity. But advocates argue that these questions over value, plus unscrupulous behaviour such as money laundering, market manipulation and scams, exist in traditional art markets anyway.

“An NFT does everything that traditional art does but better, other than being able to hold it in your hand. It has colour range, movement, provenance in a way that does not exist in real art,” says Schmrypto.

To date, the NFT market remains tightly held by a few players, many of whom have already been involved in crypto. But some maintain that the technology, the social media infrastructure surrounding them and the fact that transactions can be traced on the blockchain make it easier to message and connect with an artist, ultimately having a democratising effect.

“You have that direct connection with communities, it’s almost like the communities are able to choose what artists are popular rather than curators — and that’s creating a lot more diversity of art and artists,” says Naayem. “In the same way we went from autocracies and feudalism in our real life to democracies, the same thing is happening in our digital lives.”

Read full story on The Financial Times