The family of Russian modernist Wladimir Baranoff-Rossiné is auctioning off a non-fungible token that happens to come with a 100-year-old painting.

The art market has not been kind to the late Wladimir Baranoff-Rossiné (1888-1944), an avant-garde artist whose sculpture sits in the permanent collection of the Museum of Modern Art in New York. Since June 2011, art by Baranoff-Rossiné has come to auction 100 times; about 60% of it didn’t sell, according to data from Artnet’s price database.

This is a stark contrast from his marketability just 13 years ago, when a painting of his sold for £2.7 million (roughly $5 million at the time) at Christie’s in London. “The bottom has totally fallen out of his market,” says James Butterwick, a dealer in Russian paintings based in London. “I’ve had access to serious works by Baranoff, and I could offer, and did offer, them to serious collectors. They weren’t interested.”

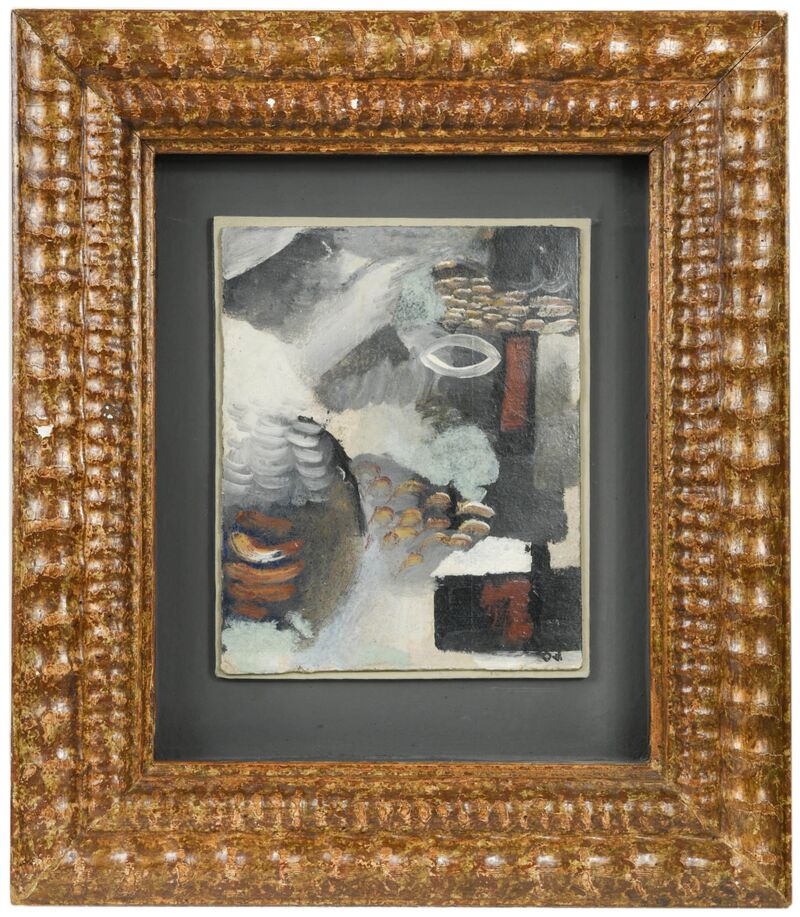

Now Baranoff-Rossiné’s descendants, who have a large collection of his work, are taking his market into their own hands. They’re auctioning an abstract painting from 1925 tied to an NFT, or non-fungible token, through Mintable, an online NFT marketplace that recently received an investment from billionaire Mark Cuban. The painting has remained in the family’s hands since it was created.

Additionally, nine digital-only pictures of other Baranoff-Rossiné paintings will be sold as NFTs in three auctions and six limited-edition sales beginning on March 25; the family will retain ownership of the original artworks.

“In terms of the NFT, it’s about being able to showcase my grandfather’s work to a different audience—and a wider audience,” says the painter’s grandson, also named Wladimir Baranoff-Rossiné. “It’s interesting: You’ve got the Beeple NFT selling at Christie’s, and we’re the opposite—the fine art piece is selling on Mintable.”

This isn’t the first time that old paintings have been attached to new technologies. Multiple companies already help authenticate, categorize, and register art collections using blockchain technology, operating under the premise that a foolproof, theoretically unalterable provenance will be of value to art collectors everywhere.

“People do like the trackability and traceability of information,” says Nanne Dekking, a former art dealer and the founder of Artory, which provides this service.

Where companies like Artory differ from Mintable is the way they assess that information.

Dekking argues that verifiable information about an artwork is valuable. Mintable, in contrast, has priced Baranoff-Rossiné’s painting under the premise that the NFT is the artwork’s value.

“This is an auction for an NFT that happens to come with a painting,” says Zach Burks, Mintable’s founder and chief executive officer. “It’s not a painting that’s auctioned that comes with [an] NFT.”

It might sound like a semantic distinction or, depending on your viewpoint, an utter disregard for artistic and aesthetic merit. But as more “traditional” artists attempt to cash in on the $1 billion boom (or bubble), and prices rise to stratospheric levels, determining and justifying these artists’ prices has become an increasingly pressing issue. Should all works associated with an NFT command a premium? Or should it be the reverse?

“You have to start with the artwork and use the underlying technology as a tool,” says Dekking. “Not the other way around.”

Price Ambiguity

Unlike at most fine art auctions, the Baranoff-Rossiné painting doesn’t come with an estimate, just a starting bid of 6.5 ETH, which—as of 4:45 p.m. East Coast time on Tuesday—was worth about $11,050.

“The estimate is hard, because there’s no estimates for any NFTs,” says Burks. “That’s just not how NFTs work.”

But it is how art auctions work. Estimates serve, generally speaking, as some form of price guidance: Even if the range isn’t exact (and, given that auction houses regularly suppress valuations to entice bidders, they rarely are) estimates give a decent sense of what comparable objects have sold for in the past.

Buyers on Mintable’s site have no such guidance, aside from a line about the auction result from 2008, “the 23rd most expensive painting ever sold at auction by a Russian painter,” though the fine print in the site they link to, artinvestment.ru, notes that its own information is incorrect. If it actually listed the top-selling works by Russians, Mark Rothko would sweep the entire list; instead, the ranking is reduced to “one artist—one picture,” the site reads.

The younger Baranoff-Rossiné emphasizes that the auction house’s price structure is out the family’s hands and, in a subsequent email, points out that the Mintable page links to his family’s website, which in turn has multiple links to the Artnet database. “We’re very transparent about the whole collection, and we’ve made sure all the important information is available to anyone,” he says.

Burks says it is “unlikely” that “someone is just buying this for the painting itself and not the NFT.”

Given that they have to pay in crypto-currency, he explains, “it’s most likely not going to be a traditional art collector, and they’re going to be a crypto-native user. But there’s still due diligence when you do anything, whether it’s buying shoes on Amazon or a $70 million artwork by Beeple.”

Finding Value

The digital images tied to NFTs present a separate valuation question. Generally speaking, NFTs act as a certificate of authenticity, thereby creating an “original” digital artwork worth more than other identical copies circulating online. It’s why a screenshot of a tweet can sell for $2.9 million.

But what happens when those certificates of authenticity are for copies of the artwork, rather than the original?

Baranoff-Rossiné suggests people approach these digital images as limited-edition postcards or posters, just as they buy limited-edition prints or photographs. “It’s like printing a one-off series of 100 postcards,” he says. “It’s exactly the same principle.”

The digital NFTs aren’t priced like postcards, though. The starting bid is currently set at 1.32 ETH, or about $2,238 per image, “a purely random number,” Burks says. “We don’t want to cut off people who say it’s already above [their] budget, but we also don’t want to start too low.”

And while the $69 million Beeple artwork started far lower, at just $100, Burks says, “I think Christie’s made a big mistake starting it at $100. That’s what high-value net worth people think about it—they value something based on the starting price.”

Given the prices that recent NFTs commanded, perhaps Burks’s high starting bid isn’t unreasonable, says Artory’s Dekking. “If they create an NFT relating to the image of a [physical] artwork, it’s basically like a poster of the Mona Lisa you buy in front of the Louvre. That’s fine, people can pay whatever they want for things.” But, he adds, “for a purely art historical value creation, it doesn’t make a lot of sense to me.”

Fundamentally, the entire exercise was meant as an experiment, says Baranoff-Rossiné, “to do something that’s never been done before” as a way “to mix old and new.”

The family, he continues, considers this sale a novel strategy to bring his grandfather’s practice into the 21st century. “We’re showcasing my grandfather’s work in a never-before-seen way,” he says. “Its a new medium, and it’s a new technology.”

Whether it will be a new market, he acknowledges, remains an open question. “Could one argue that it should go for slightly more because it does have [an NFT]?” he asks. “I think that would be a fair point.”

Read full story on Bloomberg