The negotiator entered the chatroom four days after the attack. Hackers had locked down several servers used by the epidemiology and biostatistics department at the University of California at San Francisco, and wanted a $3 million ransom to give them the keys.

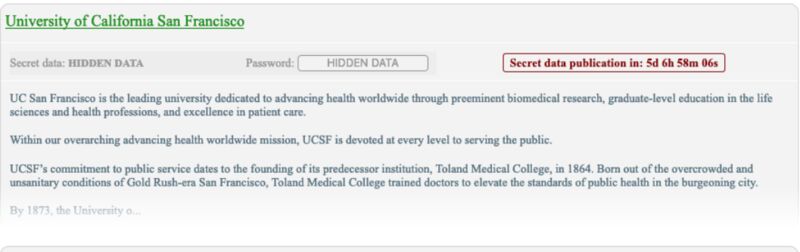

On Friday, June 5, at 6:50 p.m., they directed a UCSF negotiator to a webpage on the dark web—meaning beyond the realm of Google—that listed a dozen or so sets of apparent victims and demands. The whole thing looked oddly like a customer service portal. Just below the university’s entry was a flashing red timer counting down to a payment deadline. It read: 2 days, 23 hours, 0 minutes. If the counter reached zero, the ransom message said, the price would double.

In a secure chat that the hackers set up with a digital key, the UCSF negotiator said the attack couldn’t have come at a worse time. The department was racing to try to help develop some kind of treatment or vaccine for Covid-19, the negotiator said, and hinted that the researchers hadn’t taken the time to duly back up their data. “We’ve poured almost all funds into COVID-19 research to help cure this disease,” the anonymous negotiator typed in the chat, pleading something between poverty and force majeure. “That on top of all the cuts due to classes being canceled has put a serious strain on the whole school.”

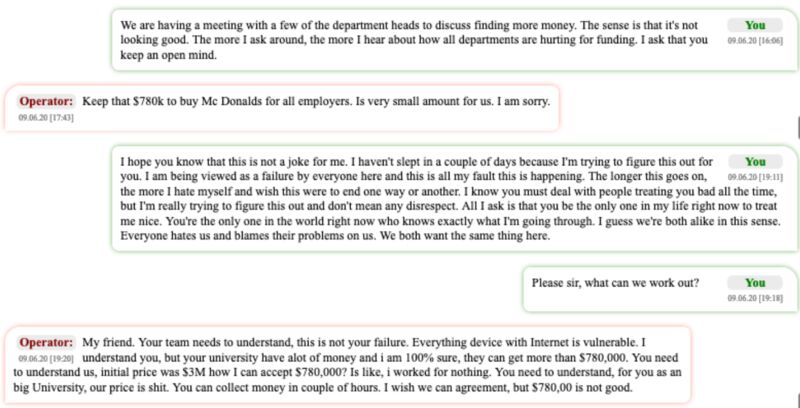

The hackers’ representative, who went by the handle Operator, said a school that collects more than $7 billion in revenue each year, one with negotiators, lawyers, and security consultants on hand, should be good for a few mil. “You need to understand, for you as a big university, our price is shit,” Operator said. “You can collect that money in a couple of hours. You need to take us seriously. If we’ll release on our blog student records/data, I’m 100% sure you will lose more than our price what we ask.” By that time, the hackers had shared a sample of data from the stolen servers indicating that they did indeed have sensitive material.

Bloomberg Businessweek received a complete transcript of the chat between Operator and the UCSF negotiator from a person with access to the chat’s digital key. Such keys tend to be distributed to members of the internal crisis response team, law enforcement, and private consultants. The university confirmed the breach but said the transcript shouldn’t be taken at face value because “the statements and claims made by either party were in the context of a negotiation.” Whatever its exaggerations, the transcript provides a rare look into the kinds of secretive ransomware attacks usually portrayed impersonally through FBI statistics, regulatory filings, and official statements. (Victims don’t usually like to admit that hackers beat their security, or that they paid off the crooks.) With the affect of a used-car salesman, Operator—probably based somewhere safely out of reach of U.S. law enforcement—led a negotiation that bore a lot of similarities to an old-school, flesh-and-blood kidnapping. The main difference was that the hackers he represented had swiped data, not people.

In some ways, Covid-19 has turbocharged the ransomware business that has proliferated, especially in Russia and Eastern Europe, over the past several years. The pandemic has made high-value targets out of universities, hospitals, and labs with access to data that are used to analyze new potential treatments or document the safety of vaccine candidates. ( Recent victims include Hammersmith Medicines Research, which conducts clinical trials for new medicines, and antibodies researcher 10X Genomics Inc., though Hammersmith says it repelled the attack and 10X says its business suffered no substantive impact.) It has also offered a bit of a coming-out party for some of the many ransomware groups that spent 2019 trying to professionalize their operations with a faux-corporate business model, complete with press releases, public websites, and even statements laying out ethical standards.

There’s more at stake in this calculus than just garden-variety scams, too. The U.S. Department of Justice has said that Chinese state-sponsored hackers are targeting global institutions conducting coronavirus research in order steal data that might lead their country more quickly to a vaccine. The DOJ investigation resulted in the July indictment of two hackers linked to Chinese state security for attacking computer systems connected to Covid-19 research. In the U.K., the National Cyber Security Centre documented a surge in state-sponsored attacks on British research institutions focused on Covid-19, and attributed much of that increase to Russia, Iran, and China.

UCSF hasn’t linked the attackers—whose English was littered with grammatical tics common among native Russian speakers—to any foreign state actors. The university said in a statement following the hack that the attack didn’t hurt its Covid-19 work, although the lost data were “important to some of the academic work we pursue as a university serving the public good.” (The FBI, which typically handles U.S. ransomware cases, referred questions about the hack to the university.) During the standoff, the negotiator told the hackers that the university didn’t know what was on the locked computers. Yet the transcript suggests that whatever the data were, the university was desperate to account for it.

According to the hackers’ dark web blog, the ransomware used to attack UCSF came from Netwalker, a hacking operation that has boomed since last fall. Netwalker malware can be leased by would-be attackers as a kind of franchise program. In March, the group posted a dark web want ad to recruit new affiliates. The qualifications included: “Russian-speaking network intruders—not spammers—with a preference for immediate, consistent work.” In June, a further ad prohibited English speakers from applying, according to Cynet, a digital security company in Tel Aviv.

Although ransomware gangs have seized the pandemic as an opportunity, they tend to play a certain amount of Good Cop, too. In a March 18 press release, a big ransomware group known as Maze offered victims in the medical industry “exclusive discounts” on ransoms. In a blog post the following month, the group declared, “We are living in the same economic reality as you are. That’s why we prefer to work under the arrangements and we are ready to compromise.” (There’s no evidence that Maze ever provided any such discounts.)

UCSF had no way of knowing with any certainly whether the hackers would deliver on their promise to restore the locked-down computers upon payment, a risk inherent in ransomware attacks. Some corporate victims hire professional negotiators in the hope that they’ll be better able to guarantee a happy ending while saving a few bucks. Others try to work it out themselves. UCSF said in its statement that it chose to retain a private consultant to support the “interaction with the intruders,” but declined to identify a company or individual.

With 2 days, 22 hours, and 31 minutes on the clock, the UCSF negotiator asked for a two-day extension so that “the university committee that makes all the decisions” could meet again. This is a common tactic for victims exploring their options before resorting to payment, but somewhat surprisingly given the school’s lack of leverage, the hackers agreed—on the condition that the school double its payoff to $6 million. “I expected Operator to say, ‘You know you’re under attack, right?’ There are no weekends off in a cyberattack,” says Moty Cristal, an experienced ransomware negotiator in Tel Aviv who reviewed the transcript. “But in this case, the bad guys were almost enjoying the conversation. It was part of the game.”

Playing for time can help ransomware victims better evaluate the threats to their networks and data. Kevin Jessiman, chief information officer for Price Industries, a Canadian air ventilation manufacturer, says the negotiator his company hired last year enabled his team to diagnose the hack they’d suffered and explore their options. “Once we were confident that enough of our system could be restored, we ceased correspondence,” says Jessiman, adding that Price stopped talking to the attackers in about 36 hours. Even though the cost of restoring and updating its security system was millions of dollars greater than the ransom demand, he says, Price declined to pay the crooks.

UCSF figured out that its hackers had managed to encrypt data on as few as seven servers, according to a person familiar with the investigation, who spoke on condition of anonymity for fear of retaliation. The attackers had copied at least 20 gigabytes of data from the machines, and so had some idea what they contained.

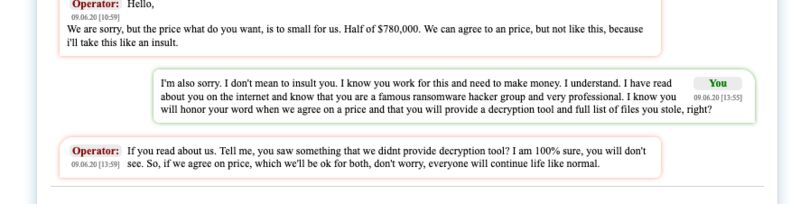

Throughout the negotiations, the university representative was careful to ply Operator with compliments. Experts say that while this is a transparent, 101-level negotiating strategy, it also works. “I’m willing to work this out with you, but there has to be mutual respect. Don’t you agree?” said the negotiator, according to the transcript. “I have read about you on the internet and know that you are a famous ransomware hacker group and very professional. I know you will honor your word when we agree on a price, right?”

These appeared to be magic words. “We are 100% about respect, never we will disrespect a client who talk to us with respect,” said Operator. “Do not offer anything ridiculous.” So naturally, the negotiator’s first offer was something close to ridiculous. The committee “said that I can submit a request for the max amount of $780,000, but I’d be lucky if I got even half of it.”

The hacker scoffed at $390,000. This was such an insulting offer, Operator said, that the hacking group threatened to blow the whistle on UCSF’s loss of student and faculty data to the Federal Trade Commission. “I suggest you re-consider another offer and this time, a serious one.”

It was an empty threat, and the negotiator called Operator’s bluff. “The FTC is not a concern for us. We would just like to unlock our computers to get our data back. I know you want to make a lot of money here, I get it, but you need to understand that we don’t have this much cash sitting around,” the negotiator said.

It was 10:46 p.m. on June 9 in San Francisco, and the two had been talking for four days.

Dragging out the negotiations might have been helpful to the hackers, too, says Cristal, the ransomware negotiator, who adds that in Covid-era attacks, there’s more at stake than money. Time to examine their bounty might have allowed Operator’s team to identify lucrative research or intellectual property worth auctioning off. Attackers affiliated with a large-scale criminal enterprise such as Netwalker may also have their own bureaucracy to wade through, Cristal says.

After standing pat at $390,000 for a day, the UCSF negotiator came back with an offer of $780,000. Operator wasn’t impressed. “Keep that $780k to buy Mc Donalds for all employees. Is very small amount for us. I am sorry,” the hacker said. “How can I accept $780,000? Is like, I worked for nothing.”

At this point, the negotiations became highly emotional, even personal. “I hope you know that this is not a joke for me,” the negotiator replied. “I haven’t slept in a couple of days because I’m trying to figure this out for you. I am being viewed as a failure by everyone here and this is all my fault this is happening.”

“The longer this goes on, the more I hate myself and wish this were to end one way or another,” the negotiator added. “Please sir, what can we work out?”

There’s no real evidence that this was anything more than a negotiating tactic. For that matter, it’s unclear whether either party was really a single person; both could just as easily be several people working in shifts. Still, Operator played along: “My friend, your team needs to understand this is not your failure. Every device on the internet is vulnerable.”

The UCSF representative responded, “I hear you and thank you for thinking I’m [not] a failure. I wish others here would see the same thing.”

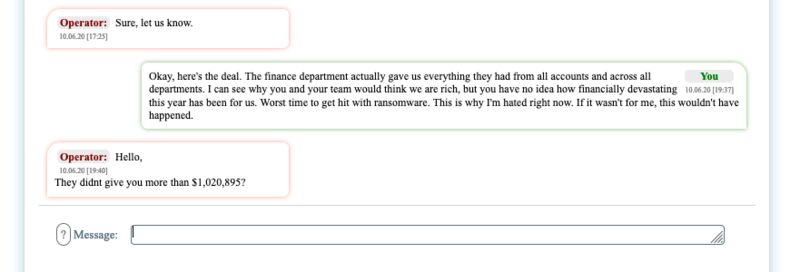

The next morning, June 9, UCSF offered just over $1 million. Operator countered with $1.5 million. With both sides perhaps sensing that a deal was close, the university’s negotiator played one last card: “The good news that I wanted to share is that a close friend of the school knows what’s going on and has offered to help and donate $120k to help us. We normally can’t accept these donations, but we’re willing to make it work only if you agree to end this quickly. Can we please end this so we both can finally get some good sleep?”

That was good enough for Operator, who responded, “When can you pay?” The two had been talking for almost six days.

The negotiator and Operator had an agreement: $1.14 million, worth about 116 Bitcoin. UCSF would spend another day and a half clearing the deal on its side and buying the Bitcoin. Along with access to the decryption key, the deal included a commitment by the hackers to transmit all the data they had stolen from the university’s network, presumably so UCSF could determine what data the hackers had in their possession and could possibly sell. It would take the attackers almost two nerve-wracking days to decrypt, transmit, and show they’d deleted their copies of the files, but they would deliver at 2:48 a.m. on June 14.

With the deal done, Operator indulged a little professional curiosity about who had really been sitting at the other keyboard, asking, “Which recovery company are you?” The negotiator didn’t answer.

-Read the feature article at Bloomberg