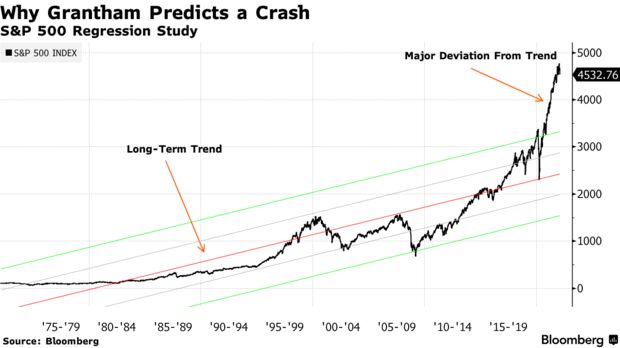

Jeremy Grantham, the famed investor who for decades has been calling market bubbles, said the historic collapse in stocks he predicted a year ago is underway and even intervention by the Federal Reserve can’t prevent an eventual plunge of almost 50%.

In a note posted Thursday, Grantham, the co-founder of Boston asset manager GMO, describes U.S. stocks as being in a “super-bubble,” only the fourth of the past century.

And just as they did in the crash of 1929, the dot-com bust of 2000 and the financial crisis of 2008, he’s certain this bubble will burst, sending indexes back to statistical norms and possibly further.

That, he said, involves the S&P 500 dropping some 45% from Wednesday’s close — and 48% from its Jan. 4 peak — to a level of 2500. The Nasdaq Composite, already down 8.3% this month, may sustain an even bigger correction.

“I wasn’t quite as certain about this bubble a year ago as I had been about the tech bubble of 2000, or as I had been in Japan, or as I had been in the housing bubble of 2007,” Grantham said in a Bloomberg “Front Row” interview. “I felt highly likely, but perhaps not nearly certain. Today, I feel it is just about nearly certain.”

In Grantham’s analysis, the evidence is abundant. The first sign of trouble he points to came last February, when dozens of the most speculative stocks began falling. One proxy, Cathie Wood’s Ark Innovation ETF, has since tumbled by 52%.

Next, the Russell 2000, an index of mid-cap equities that typically outperforms in a bull market, trailed the S&P 500 in 2021.

Finally, there was what Grantham calls the kind of “crazy investor behavior” indicative of a late-stage bubble: meme stocks, a buying frenzy in electric-vehicle names, the rise of nonsensical cryptocurrencies such a dogecoin and multimillion-dollar prices for non-fungible tokens, or NFTs.

“This checklist for a super-bubble running through its phases is now complete and the wild rumpus can begin at any time,” Grantham, 83, writes in his note. “When pessimism returns to markets, we face the largest potential markdown of perceived wealth in U.S. history.”

It could, he said, rival the impact of the dual collapse of Japanese stocks and real estate in the late 1980s. Not only are equities in a super-bubble, according to Grantham there’s also a bubble in bonds, “the broadest and most extreme” bubble ever in global real estate and an “incipient bubble” in commodity prices. Even without a full reversion back to statistical trends, he calculates that losses in the U.S. alone may reach $35 trillion.

Grantham is a dyed-in-the-wool value manager who’s been investing for 50 years and calling bubbles for almost as long. He knows his predictions are fodder for skeptics. One obvious question: How could the S&P 500 advance 26.9% in 2021 — its seventh-best performance in 50 years — if stocks were poised to plummet?

Rather than disprove his thesis, Grantham said the strength in blue-chip stocks at a time of weakness in speculative bets only reinforces it.

“This has been exactly how the great bubbles have broken,” he said. “In 1929, the flakes were down for the year before the market broke, they were down 30%. The year before they’d been up 85%, they had crushed the market.”

Seeing the same pattern that played out in every past super-bubble is what gives him so much confidence in predicting this one will implode similarly.

Grantham pins the blame for bubbles of the past 25 years mostly on bad monetary policy. Ever since Alan Greenspan was Fed chairman, he argues, the central bank has “aided and abetted” the formation of successive bubbles by first making money too cheap and then rushing to bail out markets when corrections followed.

Now, investors may no longer be able to count on that implied put. Inflation running at the fastest clip in four decades “limits” the Fed’s ability to stimulate the economy by cutting rates or buying assets, Grantham said.

“They will try, they will have some effect,” he added. “There is some element of the put left. It is just heavily compromised.”

Under these conditions, the traditional 60/40 portfolio of stocks offset by bonds offers so little protection it’s “absolutely useless,” Grantham said. He advises selling U.S. equities in favor of stocks trading at cheaper valuations in Japan and emerging markets, owning resources for inflation protection, holding some gold and silver, and raising cash to deploy when prices are once again attractive.

“Everything has consequences and the consequences this time may or may not include some intractable inflation” Grantham writes. “But it has already definitely included the most dangerous breadth of asset overpricing in financial history.”

Read full story on Bloomberg