Money is edging toward its biggest reinvention in centuries. Modern technology and even the coronavirus pandemic are pushing consumers to go cashless, and with alternative concepts like Bitcoin taking hold, central banks are acting quickly to ensure they don’t fall behind.

Their promise is a payment system that is safer, more resilient and cheaper than private alternatives. The central banks of the Bahamas, the Eastern Caribbean Currency Union and Nigeria have already become pioneers in central bank digital currency, or CBDC, while China, the euro area and others are experimenting in the field.

The U.S. Federal Reserve and Bank of England, meanwhile, are proceeding far more cautiously.

1. What would central bank digital money be like?

Not so different, at least on the surface, from keeping electronic money in a bank account and using cards, smartphones or apps to send that bank money into the world. The key difference is that central bank-provided money — like cash — is a risk-free asset.

For example, a physical dollar bill is always worth one dollar. A dollar in a commercial bank account, while in theory convertible into paper cash on demand, is subject to that bank’s solvency and liquidity risks, meaning consumers might not always be able to access it, or could even lose it on rare occasions. CBDCs, like banknotes and coins, would be the direct liability of the central bank.

2. How would this change payments?

CBDCs could come in more than one form, but one goal of all of them would be to make payments happen faster. In the current system, commercial banks settle their net payments with one another using central bank money, but this process is typically not instantaneous for technological and operational reasons, and therefore opens up a credit risk during the duration of the settlement.

3. What does this have to do with cryptocurrencies?

Aside from the potential technological design, not much. CBDCs are conceptually different from a cryptocurrency like Bitcoin, which is too volatile to be a store of value and insufficiently widely accepted to be useful for payments.

Bitcoin is more in the realm of a speculative asset. A key appeal among Bitcoin’s supporters is its decentralization, meaning there’s no central party that controls it, with transactions recorded on a publicly distributed ledger. CBDCs are controlled by a central bank. While some countries are experimenting with either full or partial use of distributed ledger technology, known as blockchain, for their CBDCs, it’s not a given that they will ultimately use it.

The European Central Bank, for instance, has raised concerns about the environmental footprint of running a parallel blockchain infrastructure, and already has another system which it launched in 2018 that could be more suitable.

4. What are the different kinds of CBDCs?

There are two main tracks: wholesale and retail. In retail projects, CBDCs would be issued through what would effectively be accounts at a central bank for the general public — or accounts at commercial banks working with the central bank.

A CBDC-based system has no credit risk: funds are not on the balance sheet of an intermediary, and transactions are settled directly and instantly on the central bank’s balance sheet. A retail approach could be particularly helpful for consumers who don’t have access to traditional banking services.

Some countries, such as Denmark, have ruled that out, however, as it could leave banks vulnerable to depositors potentially fleeing to central bank accounts.

Other central banks have said they will impose upper limits on holdings to prevent such financial stability risks. In wholesale projects, access to the digital currency would be limited to banks and other institutions to make payment flows within the existing financial system faster and cheaper, but with less disruption to the sector’s overall structure.

Digital Ambitions

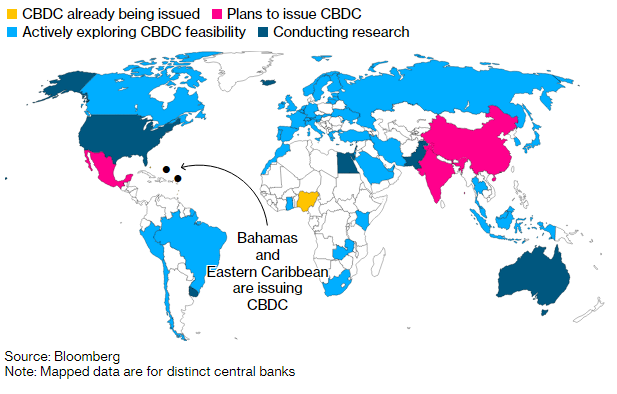

Central banks are at varying stages of developing digital currencies

5. Who’s trying this?

According to the IMF, some 100 countries are at varying stages of CBDC exploration. India surprised the payments world by announcing that its central bank will issue a digital rupee as early as the coming financial year, while China rolled out its digital yuan to athletes and spectators before the 2022 Beijing Winter Olympics to test its appeal among foreigners.

Some of the islands in the Eastern Caribbean that share a central bank have already launched their own digital currency, DCash. That was expanded to St. Vincent and the Grenadines last year after a volcano eruption forced thousands of people to be evacuated from their homes, and the roll-out was seen as an important part of rebuilding efforts.

6. Who’s not?

Matt Levine’s Money Stuff is what’s missing from your inbox.We know you’re busy. Let Bloomberg Opinion’s Matt Levine unpack all the Wall Street drama for you.EmailSign UpBloomberg may send me offers and promotions.By submitting my information, I agree to the Privacy Policy and Terms of Service.

The Fed, for one, has been slow to warm to the idea of a digital currency, but it recently took a key step by publishing a 35-page discussion paper in which it outlined a series of potential benefits.

Still, it made no firm conclusions on whether issuing such a currency was prudent and in any case said it wouldn’t proceed without support from the White House and Congress.

The Bank of Canada has also not found a pressing case for a digital currency yet, but continues to build the technical capacity to issue a CBDC, and monitor developments that could increase its urgency.

7. What would the advantages be?

If central banks can surmount the technical difficulties, digital currencies could allow for faster and cheaper money transfers within economies and across borders. They could also improve access to legal tender in countries where cash supplies are dwindling.

An IMF paper said the new currencies could boost financial inclusion in places where private financial institutions find it unprofitable to operate, and generate more resilience in regions prone to natural disasters. ECB President Christine Lagarde has argued that a digital euro could become particularly important amid a rise in protectionist policies if these led to a disruption of Europe’s predominantly foreign payment services.

For China, a digital currency offers a possible way to keep up with and control a rapidly digitizing economy. On the other hand, it could also give the government an extra tool for surveillance.

8. What are other downsides?

The risks of getting this wrong are significant, which is why most central bankers have to date trod with caution. Depending on the model of CBDC, central banks risk either cutting out commercial banks, a vital funding source for the real economy, or assuming the direct risks and complications of banking for the masses.

Problems in managing a business that’s new to them could undermine the public trust that they count on to let them pursue occasionally unpopular actions like interest-rate hikes. Also, some researchers have expressed doubts about whether current blockchain technology would be able to support a large volume of simultaneous transactions.

A People’s Bank of China official said its research showed that Bitcoin’s blockchain capacity fell well below peak demand, on China’s 2018 Singles’ Day shopping gala, of 92,771 transactions a second. Other studies have found that Ethereum handles an average of 15 transactions a second, while Visa Inc.’s network can handle 24,000.

Read full story on Bloomberg