Crypto enthusiasts are pitching a decentralized internet. The investors backing their companies have other ideas.

If you’ve spent any time around the tech industry recently, you’ve probably heard the good news about Web3, the presumed next chapter in internet history. The so-called Web 2.0 era, which was dominated by a handful of social media platforms, is over.

Web3 boosters say that instead of relying on Facebook—now rebranded Meta Platforms Inc. to avoid any of the bad vibes associated with social media—we’ll soon be communicating using decentralized services that will make the current fears of censorship by tech monopolies passé.

Web3 applications are based on cryptocurrencies, or digital tokens that are tracked on blockchains. These tokens are distributed to an app’s early investors and users, and can also be bought and sold on cryptocurrency exchanges. In theory at least, they’ll appreciate as an app takes off.

Venture capitalists invested $30 billion in crypto projects last year, according to research company PitchBook. Much of that went into Web3 startups such as Sky Mavis, developer of Axie Infinity, a blockchain-based video game; BitClout, a decentralized social network whose founder is known by the pseudonym “diamondhands”; and OpenSea, a marketplace for nonfungible tokens, the digital collectors’ items known as NFTs.

To believers—like Marc Andreessen, whose venture capital firm, Andreessen Horowitz, recently raised $2.2 billion for a new crypto fund—Web3 offers the chance to participate in a vast utopian project while simultaneously getting in on a financial boom. (Bloomberg LP, which owns Bloomberg Businessweek, has invested in Andreessen Horowitz.)

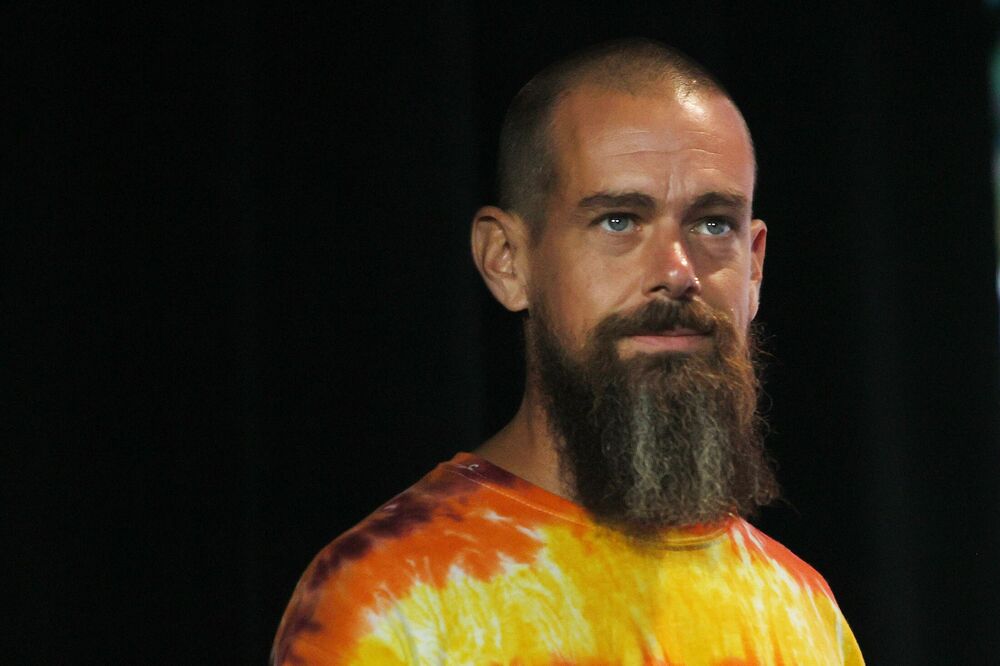

Detractors see the movement as a branding exercise designed by tech investors to preserve the mania for cryptocurrency tokens. They point out that many of the big Web3 investors are the same people who backed Web 2.0. “It’s ultimately a centralized entity with a different label,” tweeted Jack Dorsey, a Twitter Inc. co-founder and chief executive officer of Block Inc., which, until its recent blockchain-themed rebranding, was known as Square.

Andreessen responded to Dorsey’s critique by blocking him on Twitter. When Kelsey Hightower, a principal engineer at Google’s cloud computing division, tweeted that Web3 was just taking existing products and “rub[bing] some cryptocurrency on it,” an engineer at the crypto trading platform Coinbase replied: “Google’s days are numbered. We are coming for you. Tick tock.”

Hightower says he was taken aback. “This whole ‘I’m at war with your employer, and you’re going to be a casualty of this war’—that’s new,” he says.

On the other hand, successful geeks arguing bitterly about web architecture is as much an aspect of Silicon Valley’s culture as the hackathon or the fleece vest. “People are very religious about their beliefs,” says Li Jin, a co-founder of the Web3 investment firm Variant.

For Jin, a web economy in which artists and musicians sell NFTs directly to fans would allow them to reclaim power from Facebook, YouTube, and other companies. She believes today’s social media and Web3 will ultimately coexist, but the idea that a fully realized Web3 will simply replace it ratchets up emotions on both sides, she says. “We’re reaching a boiling point in terms of popular sentiment against technology incumbents and social media platforms.”

The irony is that today’s incumbents mostly got their start trying to do exactly what Web3 promises now: to disrupt a previous generation of gatekeepers in tech and media.

Last fall the entrepreneur and investor Reid Hoffman described the “wild idealism” of the early Web 2.0 era, during which he started the professional social network LinkedIn.

“The reigning ethos was to minimize rules, institutional hierarchies and gatekeeping of any kind while enabling decentralized networks and peer-to-peer interaction,” he wrote in an essay for a Knight Foundation conference on internet history.

Web 2.0 did usher in an era of decentralization, creating tools that made it easy for anyone—in theory at least—to reach an enormous audience online. But the companies running the social networks also collected huge stores of personal data, which they milked for massive financial returns. In 2016, Microsoft Corp. bought LinkedIn for $26 billion. Meta is worth more than $900 billion.

To Hoffman, this was the natural maturation phase that came after the revolution. “You have this pattern, where you get a decentralized platform and then recentralize key features that work better technologically, or as businesses, or as infrastructure,” he says. While Hoffman says he supports Web3, he predicts the same thing will happen. “Everyone says this will be decentralized forever. Well, no.”

In certain key areas, the shift Hoffman predicts is already happening. OpenSea, the NFT marketplace, recently stepped in when a New York art gallery owner, Todd Kramer, complained that a collection of 16 NFTs, mostly cartoon images of bored primates, had been stolen in a hack.

OpenSea froze the NFTs, making them effectively worthless. Although this might seem like a sensible safeguard, some users complained it was a violation of the promise of Web3, which is that no centralized entity should be able to restrict how individuals use the digital assets they possess.

By this logic, OpenSea’s ability to stop someone from selling a stolen NFT is the same as Facebook getting to decide when something counts as misinformation. Allie Mack, an OpenSea spokeswoman, said that the NFTs remain on the blockchain and that the company was simply enforcing the rules of its platform “to ensure the safety of our customers and the growth of the broader NFT space.”

The crypto world’s reputation as a crazy new financial arena where masses of random traders are getting rich may also be overstated. A recent study for the National Bureau of Economic Research showed that the top 1,000 Bitcoin holders controlled about 15% of all the currency in circulation as of the end of 2020.

And Chainalysis, a blockchain research firm, recently found that most NFT profits go to the traders who have access to so-called whitelists, which allow them to buy the new tokens before they’re offered on the open market.

Moreover, it isn’t clear that regular people will be as excited about the disruptive power of Web3 as tech investors are. The currency of the social media era was attention, which encouraged everyone, for better or worse, to go about their lives as if they were celebrities.

In Web3 everyone is a day trader. Some gamers are already expressing hostility to NFTs in video games because they just want to have fun, not manage a portfolio, and companies such as the crowdfunding service Kickstarter PBC have gotten blowback for signaling interest in Web3.

Tim O’Reilly, the investor and entrepreneur who coined the term “Web 2.0,” wrote an essay in December titled “Why it’s too early to get excited about Web3.” So far the predominant way to participate in Web3 is to bet on various tokens; the social networks of the future are still mostly hypothetical.

The history of technology, according to O’Reilly, is a repeated pattern where people get overly excited about something, creating a bubble that eventually pops, sometimes leaving something useful behind. “I love the idealism of the Web3 vision,” he wrote, “but we’ve been there before.” —With Mark Bergen

Read full story on Bloomberg