For smaller acts, NFTs offer financial gains once elusive in a music business dominated by streaming — at least for now.

A savvy cadre of recording artists has been using the new, blockchain-based digital frontier sometimes known as web3 to do what they’ve always dreamed of: Making money by making music.

The revenue they’re earning from selling their songs and music as nonfungible tokens, or NFTs, is significantly larger than the pennies they pull in from streaming services such as Spotify. At the same time, they are providing a tangible use case for elements of web3, the preferred nomenclature of venture capitalists who invest in online services built using blockchain technology, where control isn’t concentrated in a single business entity.

“I had one person buy my song for the amount it would have taken a million streams to get,” says Iman Europe, a singer-songwriter who has made 22.2 Ether (now worth almost $60,000), selling five singles and a music video as NFTs since November.

That compares with the roughly $300 a month she was earning from streaming, despite having garnered some 4 million listens across platforms. Nearly 40% of her NFT revenue was made on secondary sales, where she received a 10% cut of each resale.

Musicians like Europe took in $83 million in primary sales through NFTs last year, according to Water & Music, an organization that researches digital music innovation. Independent artists accounted for 70% of that revenue, the group found.

It’s a trend that is attracting the attention of larger investors, including 12-time Grammy Award winner John Legend. With a group of entrepreneurs and venture capitalists, he announced earlier this month that he’ll be launching a platform for artists to monetize their work using the technology.

Popularity with independent artists can partly be explained by the fact that the world of NFTs is much more accessible than landing a lucrative, corporate record deal. To release an NFT, artists attach their media — such as a song or video — to a verifiable digital token and then auction it off on an online marketplace such as Nifty Gateway or OpenSea. These operate on blockchain technology, which offers an online record of the transaction history.

Buyers get ownership of the digital asset as well as the cultural cache of having something released to a finite number of people, in some cases only to one person. At times the music is only available as an NFT; it’s a bit like owning the only copy of a CD by your favorite artist.

Alec D’Alelio, a 25-year-old living in Brooklyn, bought his first NFT of a song in February 2021. It was produced by an artist named Supa Bwe, who D’Alelio says is an influential artist in the Chicago music scene close to where he went to college at Northwestern University.

“It was still really, really early at that point for music NFTs, very few people were doing it,” D’Alelio said. “I wanted to show that people will buy this stuff, people care, people want to support.”

D’Alelio, who also produces music for fun, has since bought over a dozen NFTs of songs and albums from various artists. He estimates his total collection is worth 4.75 ETH, or about $12,000. He bought each piece for somewhere between 0.1 to 1 Ether.

Christian Kaczmarczyk, a principal at venture-capital firm Third Prime, owns more than 20 NFTs of songs from various artists. A few of the names in his inventory, such as rapper Jon Waltz, are artists he has listened to since college. Other musicians, he discovered directly on NFT platforms. He estimates his collection is worth about $150,000.

“There are some artists that I plan to never want to sell just because I’m a big supporter of their careers,” Kaczmarczyk, 27, said. But, he added, “It’s nice to be able to have this option that if it does become worth something, I could potentially sell it for a value.”

The opportunity to flip purchases for a higher price is one of the clearest financial incentives for buyers. Daniel Fowler, a music industry strategist based in London, said there is a concern about whales, entities or individuals with large sums of cryptocurrencies, buying up music NFTs. “You get into a world where people are essentially squatting on culture, in the same way that people would try and hoover up property and literally extract rent from that,” he said.

One study found the top 10% of NFT traders perform 85% of all transactions, and trade 97% of all assets at least once. Fowler, who used to work at a blockchain startup, said a key driver in the increase of NFT activity was “people having spare crypto and wanting to do other stuff with it that might be more interesting than just buying Bitcoin.”

Other complications abound. Collectors may be given bragging rights for “owning” the music or art in their NFTs, but not necessarily the copyright. It’s not always clear whether NFT collectors can alter or repurpose the music they pay for. Artists and the platforms they use say the answer is a resounding no. (Unless, they are selling open-source beats or instrumentals.)

“The convergence of copyright law with NFTs is still a great unknown,” said Kevin Greene, a law professor at Southwestern Law School who specializes in intellectual property and entertainment law. “A case is going to come at some point where some of these issues are clarified, but right now it’s a Wild West and even copyright lawyers are struggling.”

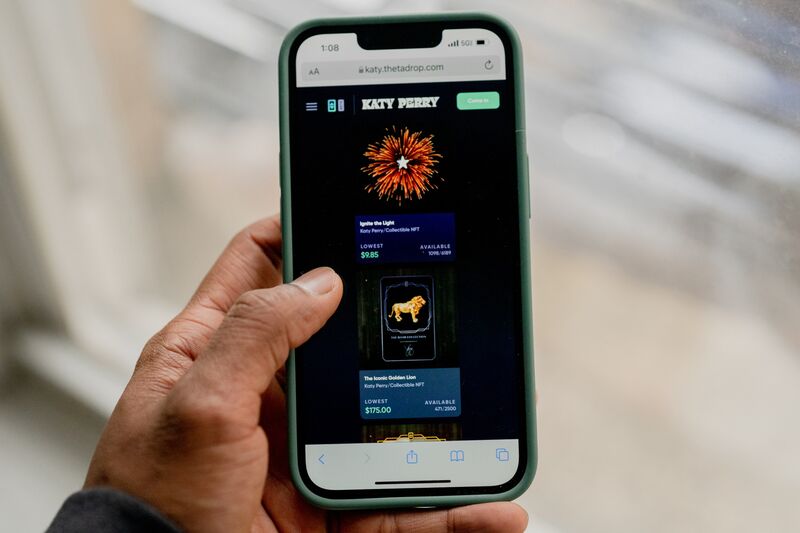

There is also the issue that other NFT projects have come to face: mainstream players entering the arena. Headliners from Katy Perry to BTS are starting to cash in. While independent artists are pulling in the majority of revenue, the gap between them and major-label artists is closing, according to Cherie Hu, founder of Water & Music.

But independent artists have something bigger acts don’t: Licensing agreements often prevent A-list artists from listing singles or albums as NFTs. Instead, stars tend to release visual art. Perry, for instance, sold a collection of behind-the-scenes photos, moving art and a physical concert prop.

Unsigned artists are able to avoid many of the legal hurdles to releasing music as NFTs. Also, because they often work with a few collaborators or alone entirely, they capture a greater portion of profits.

The business model attracted Allan Kyariga, a rapper living in Saint Paul, Minnesota, and known in the music world as Allan Kingdom. He says he stopped pursuing a full-time music career after being offered industry deals that “didn’t make sense” to take.

He started releasing NFTs when a fan recommended he sell a music video using the technology in November. After selling ten, his earnings total 15.8 Ether, or $40,000 — an amount, he says, is double the advance of a distribution deal advance for an artist of his level. One of the 28-year-old’s singles resold for as much as seven times the original price, which started at 0.1 Ether on a marketplace called Sound.xyz.

There is no guarantee that independent artists’ success with NFTs will continue. Last year was a bumper year for NFTs. With buy-in from celebrities, politicians and even socialites such as Paris Hilton, the market for these digital collectibles surpassed $17 billion. Yet with many cryptocurrencies down this year — most NFTs rely on the native token of Ethereum — some wonder if the model for musicians is sustainable.

“If this thing doesn’t get more popular anytime soon or doesn’t give incentives for people to get involved, then this will go away,” Kaczmarczyk, the music NFT collector, said.

Read full story on Bloomberg