Evidence emerging from the first central bank digital currencies (CBDCs) around the world suggests there is no one-size-fits-all model as stability and privacy are designed into systems, the head of the International Monetary Fund has said.

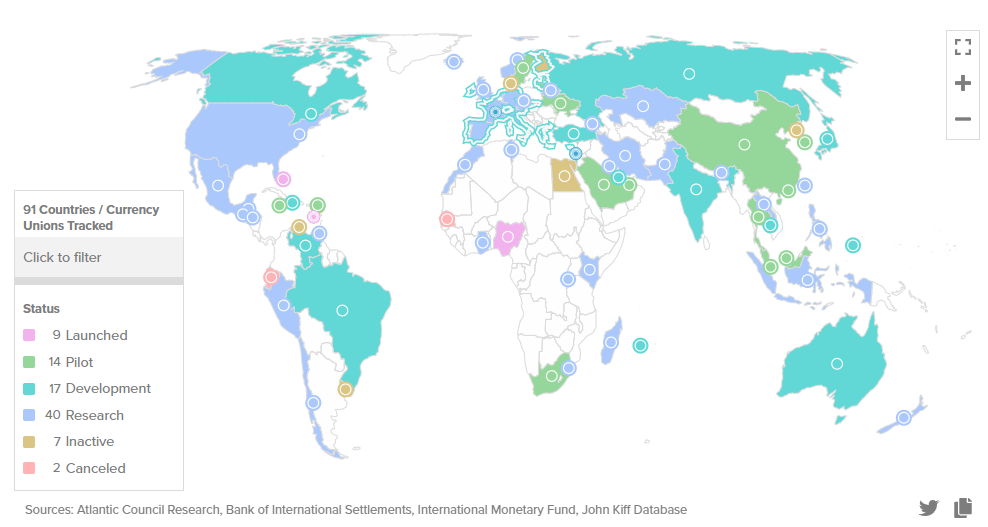

Roughly 100 countries are now looking at CBDCs, the IMF estimates, and it published a study on Wednesday looking at six nations including China, Sweden and the Bahamas where digital money is already up and running or at an advanced stage.

In a speech on the report, IMF Managing Director Kristalina Georgieva said there were a number of key lessons from these early experiences.

If CBDCs were designed “prudently” they could potentially offer more resilience, make it easier for people to have access to bank-type services and lower the cost of moving around money.

And they should be safer too, compared to “unbacked cryptoassets that are inherently volatile”, Georgieva added, referring to the likes of bitcoin as well as more regulated “stablecoins”, which are generally linked to a mainstream currency or something such as gold.

“First, no one size fits all,” Georgieva said.

Financial stability and privacy considerations also are paramount to the design of CBDCs, while there needed to be balance between developments on the design front and on the policy front.

“These are still early days for CBDCs and we don’t quite know how far and how fast they will go,” Georgieva added.

One of the main reasons central banks across the world are studying and introducing digital versions of their currencies is to avoid ‘Big Tech’ firms gaining too much control over how money flows and is used, especially with cash usage shrinking.

The Bahamas already has its digital ‘sand dollar’ up and running while China is most advanced among big economies and is doing a mass trial at the Winter Olympics now under way in Beijing, including making it available to those from overseas.

The European Central Bank in July took a first step towards launching a digital version of the euro, kicking off a 24-month investigation phase to be followed by three years of implementation.

The Federal Reserve has been more hesitant, but last month it too launched a report and 120-day public consultation to debate the advantages and disadvantages of a digital dollar.

The U.S. central bank made clear it did not favour any “outcome” yet, laying out how on one hand it could transform the financial system and speed up payments globally whereas a poorly-designed digital dollar could weaken banks, destabilise the financial system and create privacy issues.

DIGITAL DOLLARISATION

Tobias Adrian, another top IMF official who worked on Wednesday’s report, said one key worry for poorer countries was that there could be widespread “digital dollarisation” – where citizens abandon their own currencies in favour of the CBDCs from the major central banks.

“Dollarisation has always been the struggle for countries that are viewed as being unstable,” Adrian said during an Atlantic Council webinar. “But of course, once you go to a fully digital world, that kind of dollarisation, or cryptoisation, or CBDCisation could be that much quicker and more dangerous”.

Mu Changchun, director of the Digital Currency Research Institute at the People’s Bank of China also touched on the risk of digital bank runs, where savers would yank money out of commercial bank accounts and stash it at the central bank.

“We adopted the policy that we mainly pay no interest,” Mu told the webinar. “We could also introduce a potential fee to charge for large or frequent withdraws from the e-CNY system during distress or stressful scenarios”.

Read full story on Reuters