At the beginning of 2021, only a niche group of crypto enthusiasts knew what non-fungible tokens (NFT) were.

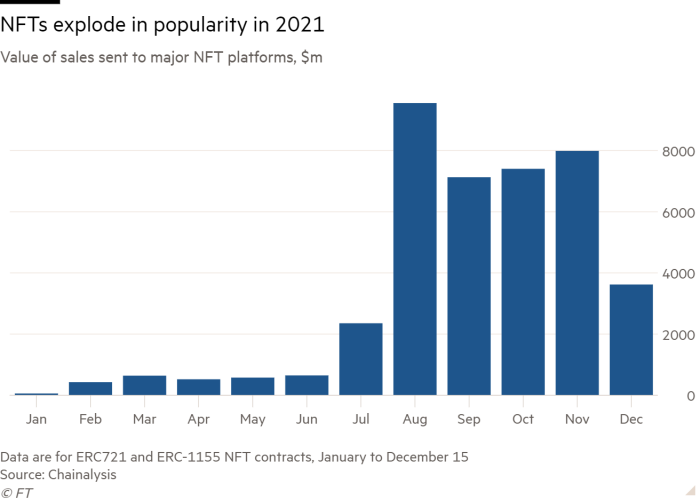

But by the end of the year nearly $41bn had been spent on NFTs, according to the latest data, making the market for digital artwork and collectibles almost as valuable as the global art market.

“This year witnessed the NFT market explode from a sub-billion-dollar market to a multi-decabillion industry,” said Mason Nystrom, research analyst at crypto data group Messari, adding that buyers were rushing to uncover art that aligns with their “digital identities”.

NFTs are essentially digital ownership certificates registered on a blockchain — an immutable record that cannot be changed or tampered with. The tokens are typically created or minted using smart contracts — self-executing contracts written into the code of a blockchain — and can be traded on the secondary market in exchange for cryptocurrency.

NFT mania hit the mainstream in March, when a collage by the artist Beeple sold for $69.3m at Christie’s, in the first sale of its kind at the auction house. The artist, whose given name is Mike Winkelmann, reacted with a tweet: “holy fuck”.

Though first popularised in the art world, corporate players from sports and music — even former US first lady Melania Trump — have also embraced the concept to cash in on the hype and find new ways to engage with fans.

The NBA, the US basketball league, created its own NFT marketplace for buying, selling and trading video highlights of its players called NBA Top Shot.

Other hits included numbered collections of NFTs that went viral, including CryptoPunks and Bored Ape Yacht Club, and which denoted the clubby status of their owners and are used as avatars on social media profiles.

“The core value is still exclusivity,” said Nystrom, noting that expensive collections also offer purchasers access to gated channels on chat platform Discord, and to meetups and parties.

“They are country club-esque: there is a high barrier to entry — a capital cost — and you are around high net worth and other individuals,” he added.

In total, $40.9bn was poured into the ethereum blockchain contracts that are typically used to create NFTs in the year to December 15, according to Chainalysis, a crypto analytics group. The total would even be higher if it included NFTs minted on other blockchains, such as Solana.

By comparison, last year the global art market was worth $50.1bn, according to figures from UBS and Art Basel.

Chainalysis found that NFTs have introduced a huge number of retail investors to the crypto world, with small transactions of under $10,000 accounting for more than 75 per cent of the market.

But much like the market for cryptocurrencies, it remains dominated by a few large players, or “whales”.

Between late February and November, there were 360,000 NFT owners holding 2.7m NFTs between them. Of those, about 9 per cent — or 32,400 wallets — held 80 per cent of the value of the market, Chainalysis found.

Stephen Diehl, a crypto-sceptic software engineer, said many whales are “sitting on hundreds of millions of dollars of crypto” from the boom in crypto prices, “looking to turn their crypto into more crypto”.

Others say they approach the market as professional traders-cum-collectors. One well-known NFT investor, known as Pranksy on Twitter, who started out with an initial investment of $600 in 2017 now has an NFT portfolio worth more than $20m, they said.

They told the Financial Times that they invest in a mix of projects, “some of which have a higher daily trading volume and others that have a more niche appeal”. Aside from “flipping” lucrative projects, Pranksy said they had “specific pieces I plan to keep as long term investments”.

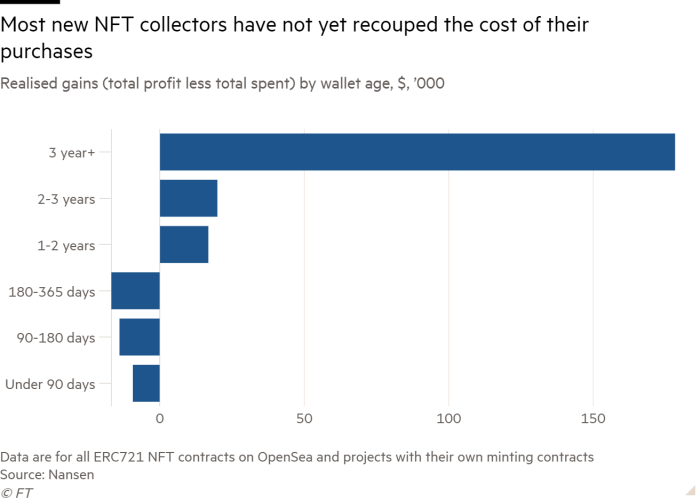

So far, most new NFT collectors on the secondary market have yet to recoup the costs of their purchases, according to an analysis for the FT by blockchain analysis platform Nansen, where early collectors have benefited from a rise in the price of the NFTs as well as in the cryptocurrency used to trade in them.

The unregulated space is also plagued by fraud, scams and market manipulation, especially because the real-world identities of buyers and sellers is difficult, if not impossible, to discover.

Analysis by Nansen found $2m of suspect activity across the CryptoPunk and Bored Ape collections in the 30 days to mid-December. Some NFTs, for example, were sold at a 95 per cent discount to the average sale price, either because of mistakes by buyers and sellers, tax write-offs or some other scam exploiting unskilled users.

Researchers have also warned that the market is likely being inflated by wash trading — when a trader takes both sides of a trade in order to give the false impression of demand.

“You can buy and sell an NFT on a public platform and make it look like there is plenty of interest in the piece when it’s just you pushing up the price,” said Rüdiger K Weng, chief executive of Germany-based Weng Fine Art.

“This happens in the traditional art world too”, he said, but added that if a manipulator consigns an artwork to Sotheby’s and attempts wash trading, they will have to pay the auction house 25 per cent of the sale, making it a costly enterprise.

“With NFTs the costs are a fraction of that,” he said, referencing the transaction fees, known as gas fees, required to mint or purchase an NFT, which can fluctuate depending on demand.

Nevertheless, there are plenty of supporters who believe that the market is maturing and will eventually offer a host of features, such as allowing artists to collect royalties in perpetuity.

“What can you do because it’s software?” asked Benedict Evans, an independent technology analyst and a former venture capitalist. “That might be things like the artist gets a share and subsequent secondary sales,” he said, pointing to early innovations in the space around music rights in particular.

Already, the so-called financialisation of NFTs is taking place in some communities — for example, using NFTs as collateral for loans, or breaking down ownership of a single piece into smaller parts, known as fractionalisation.

In the longer term, enthusiasts hope tokens will one day power ecommerce in any metaverse or metaverses, futuristic digital avatar-filled virtual worlds. Here, NFTs could designate ownership of virtual goods, be that clothing for digital avatars or art for the walls of their digital houses. Nike recently announced that it had bought a virtual shoe company to mint virtual sneakers.

Either way, the future of the NFTs market will also depend on the stance that regulators take as the freewheeling market develops.

There are concerns, even among corporate issuers, that NFTs share characteristics with certain digital investment vehicles and therefore may be considered securities by regulators.

Devika Kornbacher, partner at Vinson and Elkins, said companies looking to issue NFTs regularly ask: “Is this NFT going to be viewed as a financial instrument? Will it be considered a security from our company?”

Meanwhile, tax agencies such as the Internal Revenue Service are yet to address NFTs directly, but some experts argue that they could be deemed “collectibles”, meaning they would be subject to capital gains taxes.

“It is a looming existential issue for the whole industry,” said Pratin Vallabhaneni, partner at White & Case, of impending regulation.

Read full story on Financial Times.