Cheap power from sustainable sources and a friendly regulatory environment are a powerful combination in attracting miners.

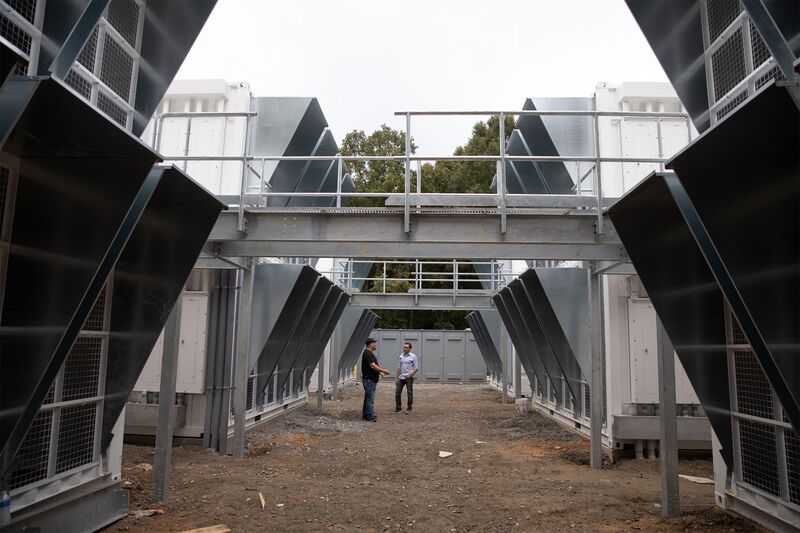

When Bitcoin miner CleanSpark Inc. bought a data center in the Atlanta suburb of College Park, the company had a problem: It wanted to switch to a cheaper, greener power provider but Georgia law wouldn’t let them.

Enter the head of the state’s power board, who stepped in last year and approved a plan under which the old data center would continue buying power from a big utility, while 15,000 mining machines on the same piece of land would be allowed to buy cleaner power sold by a non-profit generation organization at about half the price.

“At the end of the day, Georgia wants this business here,” Matt Schultz, CleanSpark’s executive chairman, said in an interview. “They’ve done everything in their power to grow Bitcoin in the state.”

The U.S. has become the world’s top destination for crypto miners after China banned the energy-intensive industry and as Russia considers doing the same. Now hundreds of thousands of mining machines worth billions of dollars are plugging into electrical grids across America, spawning an entirely new industry — complete with new tax revenue for local governments and big profits for many miners as well as concerns about power use and environmental impact. Some states are working to attract miners while others have taken a more cautious approach, or even pulled up the welcome mat entirely.

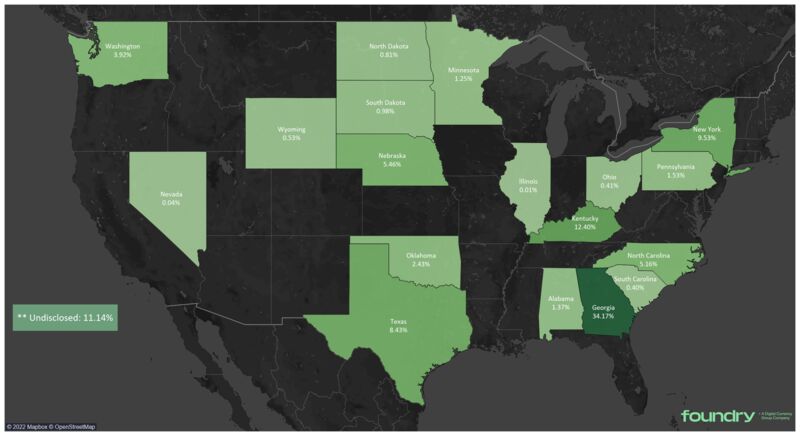

Among states that are welcoming the business, Georgia has emerged as a go-to for miners, according to Foundry, a cryptocurrency company that also operates Foundry USA, the world’s biggest mining pool.

Miners in the state were responsible for more than 34% of the computing power in the pool as of Jan. 31, almost double its share since last year’s third quarter.

Georgia is attracting miners with its relatively low power prices and large amount of nuclear and solar power, which allows mining companies to brand themselves as sustainable or emissions-free.

Regulators in the state have also built a reputation for being friendly to miners, guiding miners toward a solar program that allows companies to offset their emissions with renewable energy credits, and giving them access to day-ahead power prices so miners have enough time to throttle back their operations when rates are set to spike.

All of this helps explain why a consortium of crypto companies including Bitmain Technologies Ltd. said in September they were bringing another 56,000 miners to the state.

Other states with the largest mining operations in Foundry’s pool are Kentucky with more than 12%, followed by New York, Texas, Nebraska and North Carolina. Foundry has about 17% of Bitcoin’s global computing power, so its figures don’t represent all U.S. miners.

For example, some big Texas miners aren’t in the Foundry pool so the numbers understate that state’s share. Still, the data does provide a partial view of where miners are flocking — or where they’re avoiding, as the case may be: New York state has seen its share fall from about 20% to under 10% in the same period.

Bitcoin miners are made up of thousands of computers that run complex calculations to maintain the cryptocurrency’s network, with successful miners rewarded in the valuable and volatile virtual currency. Nobody actually goes underground and no metals are “mined” in the traditional sense.

There’s also a difference between the financial and professional services that support Bitcoin, which politicians like New York City Mayor Eric Adams are eager to attract, and actual mining, which require big data centers and consume large amounts of electricity.

Some states are pushing to attract miners with tax incentives. Kentucky passed a law last year that waives taxes on energy purchases by mining companies, while Wyoming exempted from taxes any natural gas used to power mobile mining rigs.

In 2021 alone, a total of 33 states had bills supporting their cryptocurrency infrastructures and 17 enacted new laws, according to Heather Morton, a tax policy analyst at the National Conference of State Legislatures.

New York, meanwhile, has had a hot-and-cold relationship with its miners. While the state has cheap and green hydro power and dormant industrial sites make good mining locations, lawmakers are pushing a bill that would ban mining for three years, and two towns near the Canadian border temporarily outlawed any mines.

The private equity-backed Greenidge Generation Holdings Inc. is waiting to see if the pollution permits that allow it to operate will be renewed, but the head of the state agency charged with the renewal gave some indication of his views with a tweet in September that read, “Greenidge has not shown compliance with NY’s climate law.”

Foundry invested $400 million in the U.S. last year but New York’s discouraging tone towards miners meant that only 10% of that spending was there, said Kyle Schneps, the company’s director of public policy. “New York is not expanding as quickly because there’s political and regulatory ambiguity there,” he said. “Miners are concerned about that and the possibility of a moratorium.”

Regulations that vary by state sometimes spark miners to move their operations. Sergii Gerasymovych was excited when his crypto company sold a big mining rig to an oil and gas operator with plans to mine Bitcoin in New Mexico.

But when the company started to install the mobile rig, which burns natural gas that would otherwise be flared to power about 700 miners, they learned that New Mexico strictly regulated generators like the one in the mining rig.

So the company instead trucked the rig to Texas in 2020 and set it up there instead, said Gerasymovych, the chief executive of EZ Blockchain. (New Mexico currently has no presence in the Foundry USA mining pool, while Texas is the fourth-largest.)

“On the one side of the border you can use flaring to mine Bitcoin and be praised,” he said. “On the other side of the border you’re called evil because you’re sending emissions into the air.”

Core Scientific is one of the biggest miners in the U.S. with operations in Georgia, North Carolina, Kentucky and North Dakota; it is developing another mine in Texas. Darin Feinstein co-founded the company in 2017 and looked at hundreds of sites to find the company’s first location in Marble, North Carolina, which was located in a former factory for Levi’s jeans that took advantage of cheap hydropower.

Feinstein said that while he once operated miners in Washington state, he’s since turned down dozens of deals both there and in New York because of the unfriendly approach to mining from local politicians and utilities. “Listen, we’re not moving into vicinities that don’t want us, hard stop,” Feinstein said. “We’re not going to New York, we’re not going to areas that don’t want this industry within their borders.”

Tricia Pridemore heads the Georgia Public Service Commission, which oversees electric companies and power prices in the state, and is the regulator who stepped in to make sure CleanSpark could switch to the power provider it wanted. “I don’t necessarily have an opinion on Bitcoin mining,” she said in an interview.

She sees her role as talking with miners to tell them what they should know and giving them some ways to accomplish their goals. “If they consume a lot of energy and we work with the utilities, then they’re a great fit for Georgia.”

— With assistance by Michael Bologna. Read full story on Bloomberg